“That's all your house is-- a place to keep your stuff. If you didn't have so much stuff, you wouldn't need a house. You could just walk around all the time.” ~ George Carlin

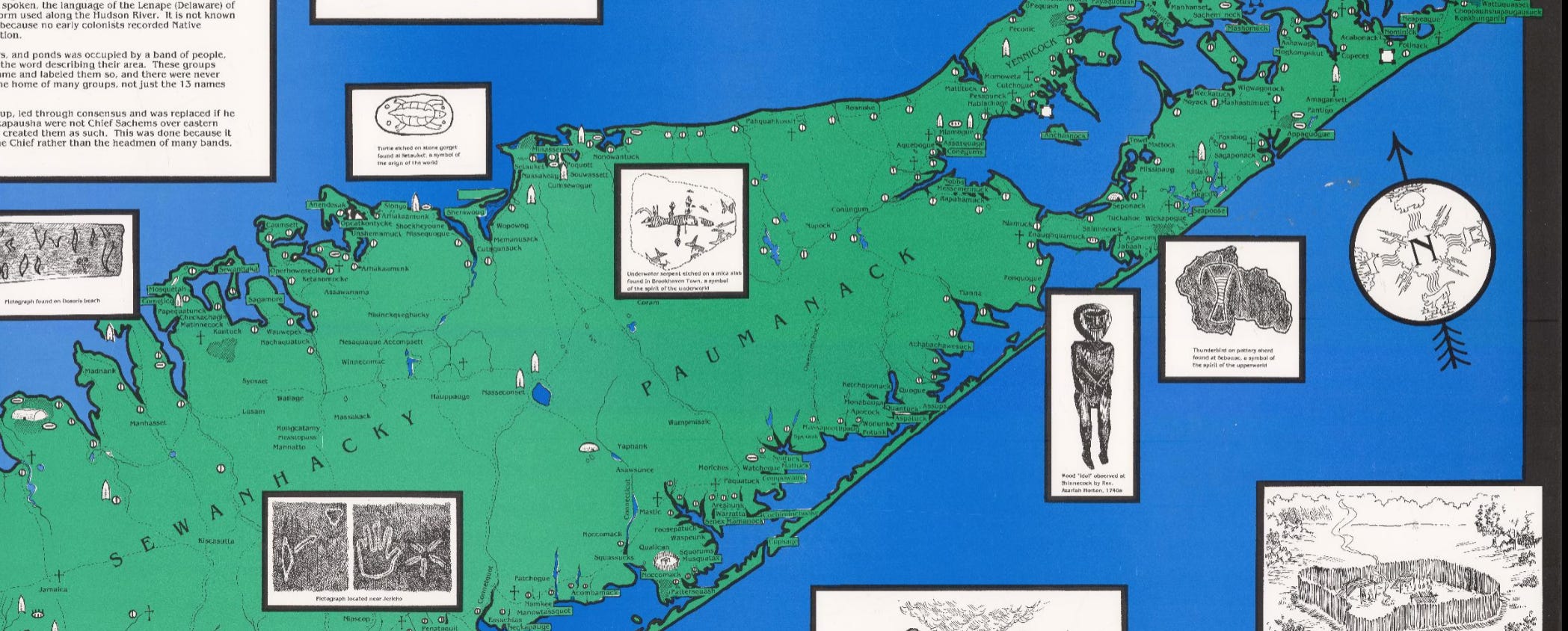

What’s most noticeable along the shorelines of the “Native Long Island” map[1] — or what the Shinnecock in translated form of Sewanhacky refer to as “purple shell place/land” and the Unkechaug, Paumanack as “land of sea god/spirit island”[2] — is the vast amount of Native Peoples and place names, whereas inland has far less.

The contrast to today is startling. The shorelines are primarily reserved for those who can afford to build houses and live there, and those who can afford to vacation or weekend there, in effect, for recreation.

As the word suggests, “recreation,” while fun, attempts to one-up the Creator’s creations—and the main travel routes are not by canoe along the shores, but primarily by a heavily trafficked road in the middle, known as the Long Island Expressway (with an acronym that’s hard to miss, LIE). Driven away from the waters (no pun intended), people got domesticated.

Aside from the natural urge for being comfy at home and sprucing up the place, herein “domestication” refers to an excessive obsession for stuff—as if it’s not ok to live as if in a Zen temple or simplified architecture of choice at home, or dress up the place with artsy bohemian decor—stuff that you yourself and friends and fellow artists make and give freely.

Rampant consumerism reflects one way that humans’ consciousness has been domesticated or dominated by societal norms and trends. “Domestic” is from Latin “domus house, from dom-o- house.”

But “house,” you may think, has nothing to do with domination. But it does:

“In ancient Rome, the domus was the type of town house occupied by the upper classes and some wealthy freedmen during the Republican and Imperial eras. It was found in almost all the major cities throughout the Roman territories. The modern English word domestic comes from Latin domesticus, which is derived from the word domus. Along with a domus in the city, many of the richest families of ancient Rome also owned a separate country house known as a villa.”

In that sense, domesticated means privileged and is inextricably linked with domination because of the two-tiered system then and even more so globally nowadays. Yet domesticated also applies to anyone and virtually everyone living under a roof. Except for “uncontacted tribes” – as news headlines are wont to call them – i venture to say that every human being has been domesticated to some degree. A dear Setalcott friend who used to live in a tent in the woods, even through winter, drank Poland Spring bottled water . . . because: “All the while, the real threat is that every stream or body of water is contaminated in the United States and the very real possibility of an uninhabitable planet is far from our consciousness.” ~ Tiokasin Ghosthorse (Cheyenne River Lakota), from Children of the Sun (2011).

From Latin domāre, from Proto-Italic *domaō, from Proto-Indo-European *domh₂éyeti, causative form of the root *demh₂- (“to domesticate, tame”).”

Further etymology includes: Master or Lord of the House. And since “lord” is from “keeper of the bread” (hlaf "bread, loaf" + weard "keeper, guardian"), it’s easy to see where the expression “breadwinner” comes from—breadwinner of the “house,” king of the little castle, the sir ruling over the madam—”Old French ma dame, literally "my lady," from Latin mea domina.” In other words, a subtext to an average introduction: ‘I’m Mr. Hlafweard and this is my dominated lady.’

While one can surely love one’s daddy, in the Latin sense he is the driving or dominating force of the house in which, stereotypically, American women play the roles of the “domesticated.” The 1950s ushered in the Age of Appliances, of which one’s status was sealed with the latest domesticated gadgets: refrigerators, stoves, and such like.

Nowadays, eating food from a corporate package is another form of domestication; at least one can give thanks (if it’s still actual food) to Mother Earth from whence the comestibles.

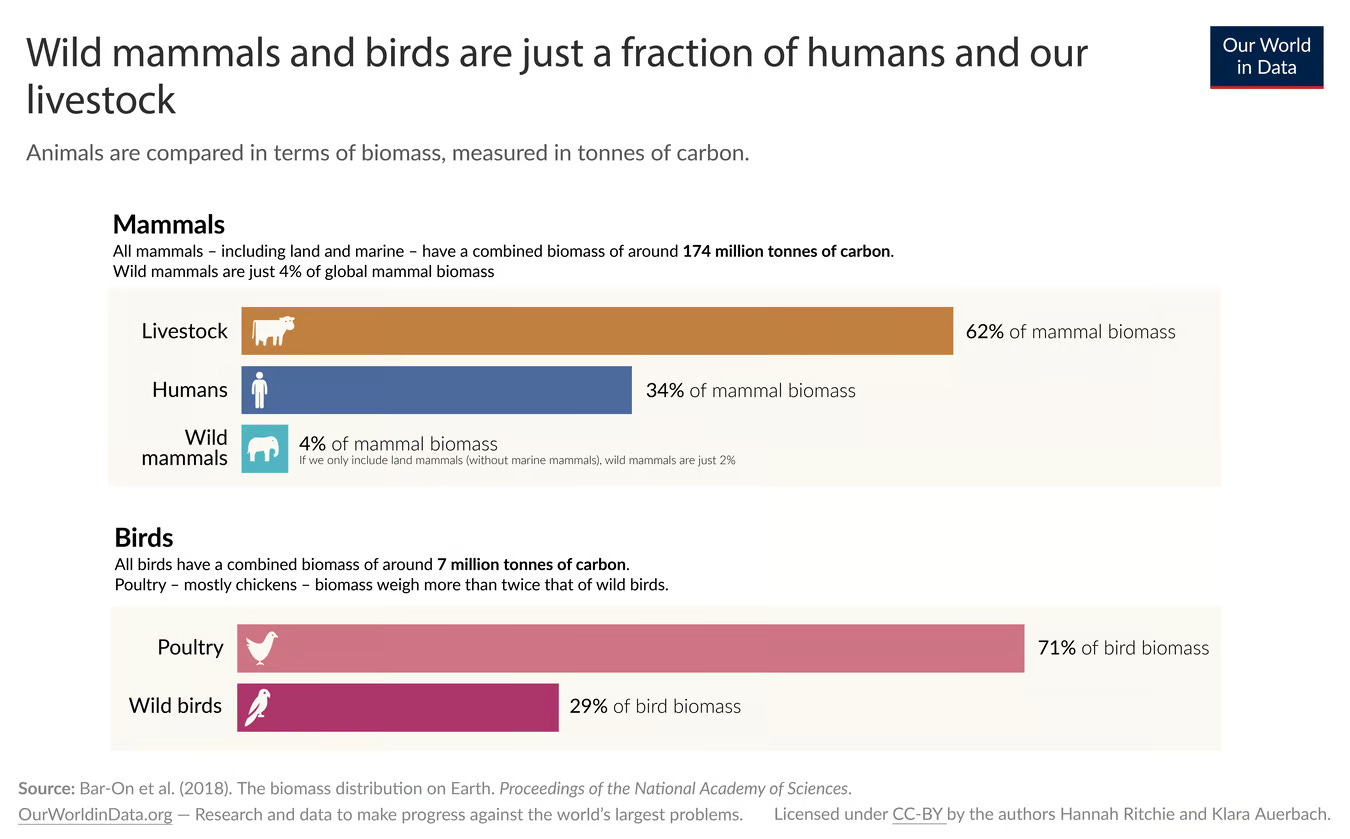

And it’s not just humans that have been domesticated; wild has become a minority:

When i have learned of wild four-leggeds being murdered, for examples, wolves and buffalo, typically the fine print finger points to the livestock industry…for their efforts to preserve their bottom line in hell.

Long before the 1950s appliance seeds of big-box stores were planted, the Allotment Act was a major force for domesticating the originally wild and free Native Peoples:

“The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887) regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the President of the United States to subdivide Native American tribal communal landholdings into allotments for Native American heads of families and individuals. This would convert traditional systems of land tenure into a government-imposed system of private property by forcing Native Americans to "assume a capitalist and proprietary relationship with property" that did not previously exist in their cultures.”

While literal common ground has been minimized under the property-owning boot, a common ground needing nurtured is with Natives and non-Natives, as both Peoples have been forced to live primarily under institutionalized forms of corporate-government domestication, abetted by the religiosity-imposed Doctrine of Discovery and Domination.

Society allows for emotional outlets loosely labeled “wild,” for examples, concerts, parties, and recreational activities like dirt-biking and boogie-boarding, yet it requires extra effort to tap into one’s wild consciousness and to have an unscripted experience.

Pulling off the road into the County Park woods with a hiking trail, the first thing i notice is the wilderness; not African safari wild, yet it’s a welcome taste — where i can see tangles of Pitch Pine thin needles and the random, strewn by the winds, bits of branches forming a quiet organization, an orderly disorder, an unmappable maze that laughs in the face of lined roadways and exact mileage to the next exit with “Gas – Food” but no longer “Phone.” A mere taste of wild yet a gulp compared with the predictability of suburban concrete routines.

Stepping out of the car for some brief deep breaths of February frigid air and looking around at trees and sky, i’m suddenly hyper-sensitive to every sound within the prevailing quietude. ‘What’s that?! . . . Oh, simply a row of dried brown leaves on a low branch’ . . . dried leaves softly rattling in the wind, in constant motion like Tibetan prayer flags praying for Spring’s thaw . . . praying for humans to remember, remember where they come from and how they truly are . . . . .

[1] “Illustrative map of Long Island centered around its native history and culture by Dr. Gaynell Stone. Indigenous groups, towns, and sites of early colonist contact are marked and drawings of artifacts and ceremonies decorate the page.”

[2] There are various spellings of each, and the latter translation learned from Chief Harry Wallace (Unkechaug Nation), at a presentation at Sachem Library, May 4, 2019.

&

Thanks, Peter! ... and part 2 in the works, interestingly pseudo-synchronously with your recent about "Baron & Femme", about Lords & Ladies, Masters & Slaves, factories...

Thanks for appreciating, April! ... and that line was a last minute add, as the ending felt like it needed something more. And thanks for sharing your poem! Plus with your comments they accentuate the two drastically different ways.